Copier and the younger generation: Free glass in the Netherlands – part 1

When you look at the work of Copier and that of his colleagues and successors, you see no rivalry or opposition between the different generations, but rather mutual exchange, stimulation and a shared effort to bring glass art to a higher level. Copier was not just a pioneer for the next generation, but he actively used his enormous talent and experience to help young glass artists.

Young talent in Leerdam

The contact between Copier and the younger generation came into existence during the Second World War, due to the establishment of the Leerdam Glass School by Copier. The aim of the school was to cultivate new artistic and artisanal talent for the Glass Factory. Copier succeeded wonderfully, not only through his own contribution, but also through his ability to attract young talent. Almost thirty years earlier, the young Copier had benefited from the fact that Cochius, director of the Glass Factory, had enabled him to attend an art education. Now it was Copier’s turn to make sure new talent was acquired for the factory. Mart Stam, architect and teacher at the Instituut voor Kunstnijverheidsonderwijs (IvKNO, Institute for Applied Arts Education) in Amsterdam introduced him to the promising young teacher Sybren Valkema (The Hague 1916 – Blaricum 1996). Valkema started working as a Glass Decoration teacher in Leerdam in 1943, where he taught Floris Meydam and Willem Heesen. In the following years Valkema, Meydam and Heesen would develop into the most important post-war glass designers in the Netherlands.

Glass Factory Leerdam

The Glass Factory Leerdam was one of the first big companies in the Netherlands that was committed to bringing together art and industry. In 1916, architect K.P.C. de Bazel was asked to design drinking sets and glassware under the inspiring leadership of director P.M. Cochius (1874-1938). During the twenties other artists followed such as architect H.P. Berlage and designers Chris Lebeau (1878-1945) and Chris Lanooy (1881-1948). Especially Lebeau and Lanooy were real ‘decorative artists’, skilled in many disciplines such as drawing, painting, ceramics and textile. Andries Copier, who was working at the factory since the age of fourteen and who became chief designer, made the decisive step to produce good and contemporary designed glass in series.

Copier also provided an important artistic stimulus by founding the Glass School. This way, Leerdam grew into the center of glass art in the Netherlands and it became internationally renowned in the field of industrial design. After the Second World War, the factory remained a testing ground for new, but also established talent. In 1960, for example, visual artist Paul Citroen (1896-1983) designed a number of unique pieces for Leerdam. Gradually independent glass studios and art schools took over the pioneering role of the factory, but in Leerdam they didn’t stop glass blowing. The craft is kept alive with glass blowing demonstrations and by inviting artists to explore new possibilities with glass. The National Glass Museum, located in the old villa of Cochius, shows the latest developments in glass art and ensures that the Glass Factory Leerdam is remembered as one of the founders of what is now known as ‘Dutch Design’.

Floris Meydam: International influence

Born and raised in Leerdam, Floris Meydam (1919 – Leerdam 2011) gained experience in the Glass Factory early on; as a sixteen-year-old he started in the advertising department, while attending Artistic Industrial Education classes in Utrecht in the evening hours. After only a year in Valkema’s Glass Decorations Class, Meydam was allowed to teach at the Glass School himself. In 1949 he became head of the design department of the factory, which made him Copier’s right-hand man. Meydam turned out to be a successful industrial designer. Already in 1952 he won the Good Design Award of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a few years later prizes followed in Brussels and Milan.

In addition to various glass drinking sets, Meydam designed the majority of the Leerdam Unica (one-offs) made in the 1950s. According to art historian and glass expert Helmut Ricke, Meydam played an important role in the development of international glass art in the 1950s. This places him among great Italian designers such as Flavio Poli and Scandinavian masters such as Per Lutken and Vicke Lindstrand. Designer Wim Crouwel wrote about this: ‘Meydam formed a bridge between the northern glass designers and those from more southern regions (…). Between the restrained pureness and freer colourfulness.’

From the 1950s Meydam experimented with bolder colours and forms and shapes and special techniques. He introduced working with a vacuum technique, which meant sucking in air during the blowing of the glass, creating a strong contrast between the interior and exterior form. Towards the end of the 1960s he was influenced by the clear geometry of minimalist artists such as Bob Bonies, Peter Struycken and Ad Dekkers. This way, he made massive geometrical objects that played a subtle game with the refraction of light.

Willem Heesen: The new chief designer

Willem Heesen (Utrecht 1925 – Leerdam 2007) attended the Glass School between 1943 and 1947, where he met Meydam and Sybren Valkema. The lessons of Valkema were especially influential on the young Heesen. Valkema, who had studied at the Koninklijke Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Fine Arts) in The Hague, did not limit himself to glass art, but was involved in various disciplines, ranging from graphic art to ceramics and textile. Valkema probably recognized Heesen’s versatile talent and encouraged him to continue his studies at the Vrije Academie (Free Academy) in The Hague. In addition to his studies, Heesen kept working at the Glass Factory, where he designed diverse glassware. From 1960 he also designed unique objects and in 1967 he became chief designer.

Heesen left the factory in 1977 to set up his own glass studio in the nearby town of Acquoy, where his enormous talent could reach its full potential. Especially the surrounding nature of the Linge was a constant source of inspiration for Heesen. Studio De Oude Horn, named after the former water pumping station at which the studio was established, quickly became a meeting place for Dutch and international glass artists. Copier also worked here frequently together with Willem Heesen and his son Bernard Heesen, a good example of the continuous interaction between different generations of glass artists.

Sybren Valkema: Versatile freelancer

As a certified art teacher, Sybren Valkema had a different approach to glass art than Heesen and Meydam. As employees of the glass factory, Heesen and especially Meydam were working with glass full time. Valkema combined his work as a freelance teacher in Leerdam with a teaching position at the IvKNO (Institute for Applied Arts Education) in Amsterdam. Soon, Valkema was promoted to assistant director of this institute, which was later renamed the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. In addition, he was also working at the experimental department of the Porceleyne Fles in Delft from 1956 to 1962, where he inspired a new generation of ceramic artists. But the world of glass with which he had come in touch with in Leerdam did not let him go.

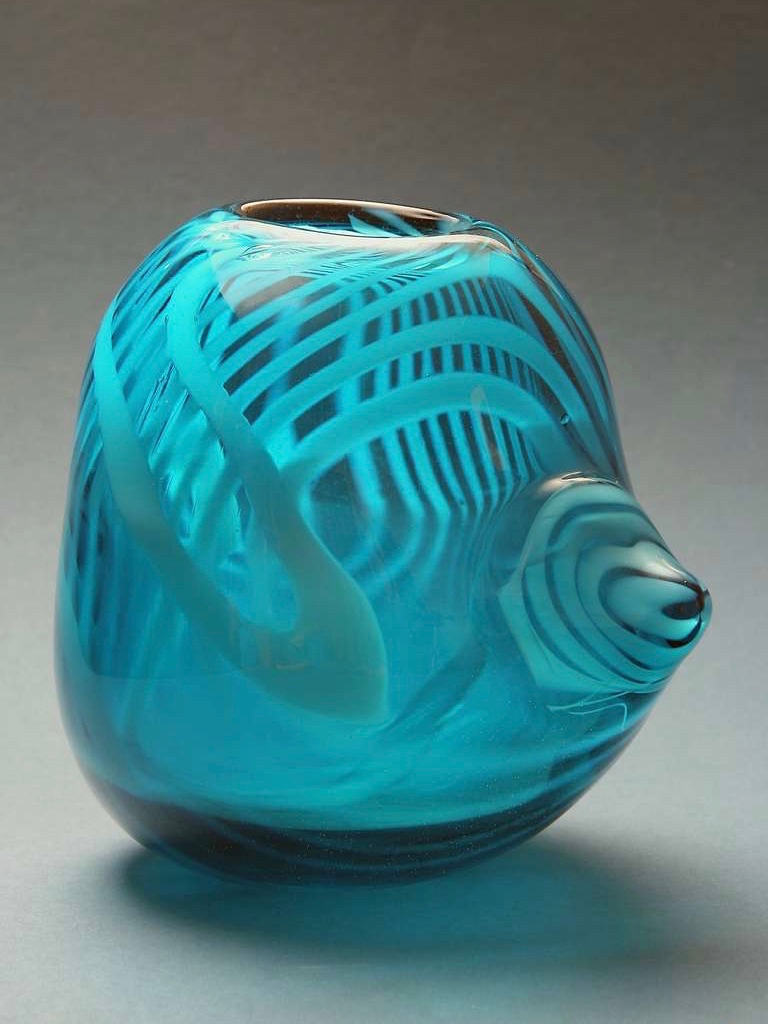

During the 1950s, Valkema designed engraved decorations, glassware and vases that were produced by the glass factory. Slowly but surely, he grew into the glass profession. In 1957 his first Leerdam one-offs were made. Valkema worked closely with master glass blower Leendert van der Linden, who once followed his classes at the Glass School. Around 1960 the first massive, freely formed and sanded masks were made. Valkema then gradually stopped designing serial objects, to design almost exclusively unique objects from 1961. In 1962 he stopped at the Porceleyne Fles so he could focus on designing one-offs and the construction of the new Rietveld Academie. Unlike Meydam and Heesen, Valkema never came into permanent employment at the glass factory, which was probably a deliberate choice.

The next blog will be about the free glass after the Leerdam Glass Factory. Read here.

Photos: Dieter Enke, Noortje Remmerswaal

© Kunstconsult – 20th century art | objects

Reproduction and distribution of this text is only allowed with correct reference.