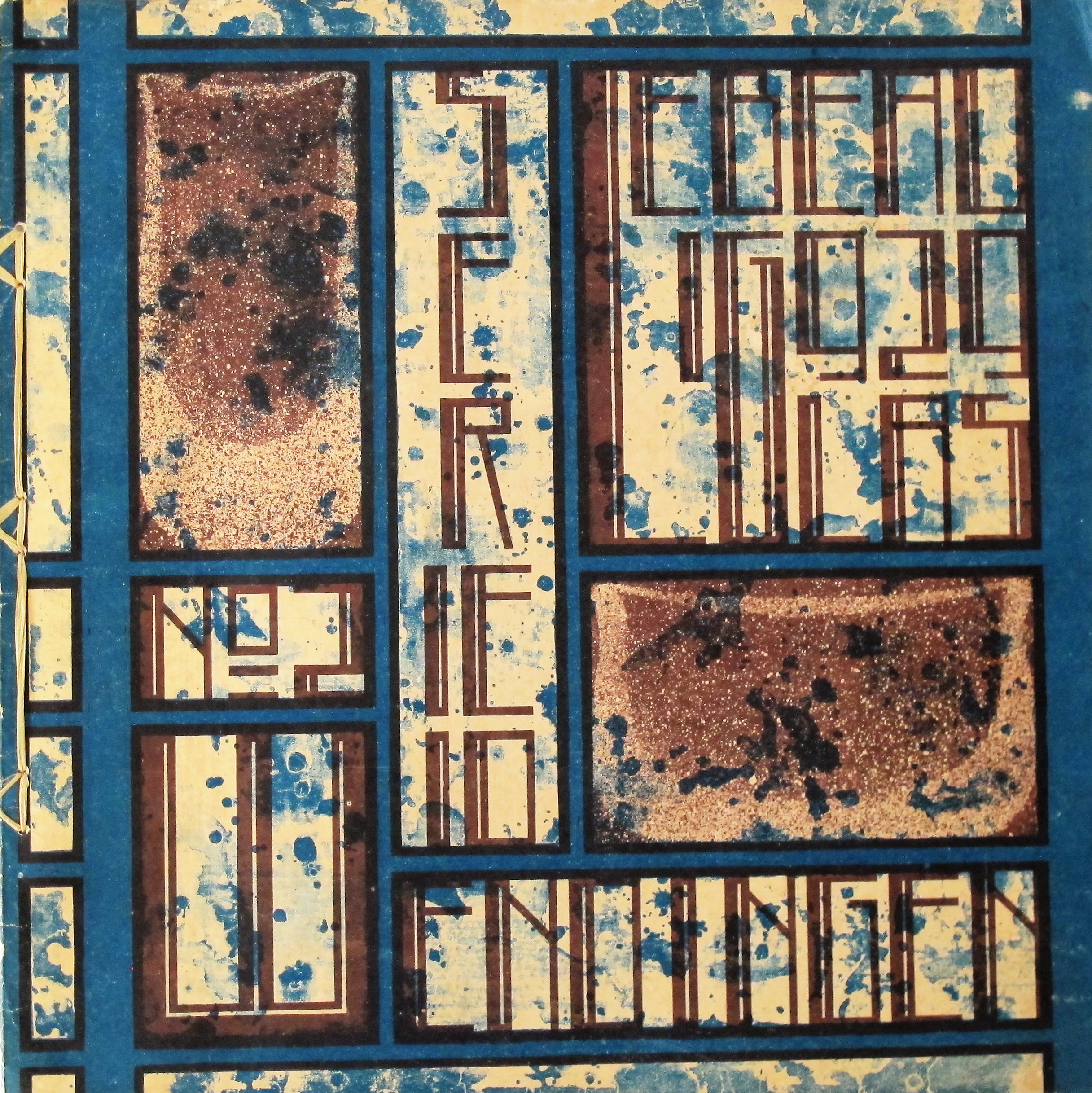

Glass artist Chris Lebeau: The alchemist and his briefcase with explosives

Armed with his ‘explosives briefcase’ and his acquired knowledge from Leerdam, decorative artist Chris Lebeau (1878-1945) went to the Bohemian glass factory Moser und Söhne in early 1926. Here his urge to experiment and his almost infinite imagination resulted in the creation of glass objects of exceptional technical and artistic quality. He returned in the winter of 1927 and 1929 to continue his artistic exploration at the Bohemian glass factory.

Chris Lebeau’s time at the Glasfabriek Leerdam laid the basis for his future Bohemian glass. This was at the beginning of 1923 with the glass blowing of one-off objects. These unique glass objects were the result of a direct and spontaneous collaboration between the artist and the glassblower. Unlike with glass in series, the emphasis with one-offs was on the experiment. No elaborated design was made beforehand; a simple sketch did the trick.

Leerdam Unica

These 'glass art objects' were not only created for aesthetic reasons. The idealistic director Cochius, who was closely involved in the establishment of the 'Association for Art and Industry' (B.K.I.) in 1924, advocated serial production, in which artists and industry collaborated on an equal level. He believed that unique pieces would also bring the technical quality of the Leerdam glass to a higher level. On the one hand, the technical skill of the glassblower would increase while at the same time the artist would gain more practical knowledge of the technique, so that he could realize even more well-thought-out designs.

After Lebeau had already designed several glass series for the glass factory since 1924, Cochius invited him in 1925 to make a series of one-offs. Andries Copier (1901-1991), who had been working on more experimental glass for more than two years, introduced the various decorative techniques: the fusing of glass wires and glass fragments, the iridescent glass and the making of various crackled glass.

Crackling technique

For iridescent glass, the glass is brought into contact with metal chlorides which are evaporated in a kiln, resulting in a pearl-like effect. This can also be achieved by burning metal salts into a glass object when it has cooled down. Crackle occurs when glass containing metal oxide is blown out. Because the thin metal layer cannot expand, it 'cracks', resulting in a crackled effect. The structure of this crackling is roughly determined by the temperature of the blown-out glass – becoming coarser when the glass object is further cooled down - while the colour is dependent on the metal oxide used.

Because disagreements arose, the cracquelé technique being one of the disputations, Lebeau's collaboration with Leerdam was short-lived. Copier accused Lebeau of having exhibited one-offs without mentioning that the technique was Copier's invention. Lebeau, in his turn, argued that Copier had simply adopted forms Lebeau had come up with. Moreover, he was outraged by the fact that his unique objects were not exhibited under his own name but as ‘Leerdam-unica’. It was for the highly principled Lebeau – who for example refused to design drinking ware since he was a teetotaler, - a reason to look for collaborations elsewhere.

Ludwig Moser and Sohne

Being renowned and all-rounded, Lebeau could almost immediately work for the Bohemian glass factories of Ludwig Moser und Sohne. Here glass blowing was at a much higher level than in Leerdam. In Bohemia, glass was traditionally blown with the intention of cutting it, which placed high demands on the quality of the crystal glass and the skill of the glassblower. In addition, whereas in Leerdam the hot glass mass was rotated while sitting and with the aid of a special workbench, in Bohemia people were standing up during the glassblowing; an insignificant fact at first sight but with major consequences. It meant that two people were needed in modelling and turning the blowpipe, which meant that the artist was much more closely involved in the production process.

In the winters of 1926 and 1927 Lebeau, on a contract basis, realized in the Bohemian glass factory a series of technically and artistically high-quality unique pieces that still make an appeal to the imagination. From his urge to experiment and his almost infinite imagination, he created a diverse palette of shapes and decorations. He introduced the techniques he learned in Leerdam with a high degree of perfection and applied them in complex combinations.

Experimental chemist

Take for example the above pictured light blue chalice vasewith a very wide rim. A vertical pattern has been realized in the crackling. To achieve this, Lebeau used a metal mold with vertical ribs in which the glass is blown out. At the places of the ribs, the iridescent glass could not expand, and the thin metal layer would not crack, while a crackling could occur between the ribs. Besides this, the rim outside the ribs has a finer crackle, which is obtained by additionally heating the glass outside the metal mold and then "swinging" it out. At the end the edge of the vase was trimmed with a blue glass wire.

Lebeau never coloured the glass beforehand. He only applied the colours during the actual making process. He did this either by melting in coloured glass - in powder form, as small shards or in the form of wires - or with the help of chemicals. Lebeau frequently used his 'explosives briefcase', as he called it, filled with chemicals that he had brought from the Netherlands. 'Lebeau is an experimenting chemist in his profession', said the painter and art critic Just Havelaar later. "An alchemist must have been among his ancestors ..."

On his way back to the Netherlands in early March 1927 Lebeau traveled via Leipzig, where Moser showed his work at the Frühjahrsmesse, a European exhibition for applied arts. The Dutch art critic Jan Voskuil writes about it in De vrouw en haar huis: 'Indeed, this glasswork is a highlight in Lebeau's oeuvre. (...) In the Czechoslovakia section (...) I saw some of Lebeau’s works, exhibited among the top works of other countries, which made an excellent impression. And no wonder, for he creates magic with his glass, it sparkles and beads (...). '

Return to the Moser factories

Although Lebeau was planning to work in Bohemen in 1928, it was only in the winter of 1929 that he returned to the Moser factories. The third and final series of Bohemian one-off pieces produced in this period have a different character from the previous glassware. While Lebeau’s previous unique objects were thin-walled and eccentric in shape, paying less attention to the 'will' of the material, the unique pieces from 1929 are specifically heavy and relatively simple in shape. Furthermore, the colours and crackling that were previously on the surface are now trapped under a layer of clear, colourless glass, which gives a completely different effect. While the unique pieces of the first series are almost opaque due to their experimental metal film, and are hardly reminiscent of glass, Lebeau seems to have paid more attention to the characteristics of the material and its intriguing brilliance and clarity in his last winter at Bohemia. The goblet on a broad flat foot, depicted below, is typical of this last series. Lebeau made several variations on this theme, of which some are represented in the collections of Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. ‘These vases grow out wide or stretch to elongated calyxes,’ Havelaar wrote in the renowned interbellum journal Wendingen: ‘He [Lebeau] loves the great form. The refinement was mainly sought in the technique itself, in the snowy crystallisations, in the smoky shady tones, in the fine brokenness of the colours.’ The idea for the 'snowy crystallizations' - an enclosed, dense crackle of light flakes - was inspired by Lebeau’s impressions of a heavy snow storm in the Bohemian hills.

Lebeau as the conductor of an orchestra

As with his earlier series, Lebeau only took part of his Bohemian one-offs back to the Netherlands, where he exhibited and sold it in 'De Bron', the art gallery in The Hague of his second partner Ditte van der Vries. The last series was exhibited under the title 'hand-formed Lebeau glass'. Once more, the wording shows that Lebeau not only supplied a design for the one-off pieces but that he was also very involved in the entire creation process. Although the artist seldomly makes the glass himself – which is in fact not the most important aspect of the work - he had a great influence on the outcome as a designer. While one of the glassblowers blew under his instructions and a second one spun the blowpipe, the Dutchman - now regulating the air supply - modelled the glowing glass mass with simple wooden or iron tools. As a simultaneous chess player, he also conducted multiple groups of workmen. 'He leads the workers as the conductor of an orchestra', said Voskuil after an interview with Lebeau. 'Each group has a piece of work in hand, of which he always determines the shape and colour. His thoughts are thus immediately realized in the matter during the action and for a large part the objects owe their freshness to this. These symphonies of glass are clearly the direct products of the flexible medium and instruments (...). The beauty of technology and the good intentions of the artist have united a harmonious whole in these objects (...). '

Acclaimed artist

Voskuils positive review can be considered as representative of the reactions in the Netherlands to Lebeau's Bohemian glass. The series were received by art lovers and connoisseurs with increasing enthusiasm. The Gemeentemuseum in The Hague and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen immediately purchased some one-off pieces while Wendingen published a special issue for Lebeau’s workin 1929. Especially the experimental element and the (particularly in the Netherlands) exceptional technical quality were praised. The increased appreciation for the work can also be seen in the prices, which strongly increased during this period. While in 1925 a Leerdam Unica by Lebeau costed only a few tenners, in 1929 the price for a Bohemian one-off objecthad already risen to several hundred guilders, which today would amount to several thousand euros.

Lebeau in the international top

In Wendingen Havelaar described Lebeau as a man who ‘renewed every area of art he laid his hands on’ and that it could be said that the artist, with his batik work, damask designs and applied graphics, played a significant part in the Nieuwe Kunst (Dutch Art Nouveau) and Art Deco. In the field of glass art, however, Lebeau is of more than national significance. What he did here, came about in only a few years (1925-1929) but is of exceptional technical and artistic quality and can compete with the international top.

It is therefore not a coincidence that in 1928 Cochius attempted to get Lebeau back to Leerdam with an enticing contract. It was in vain; the idealistic and principled Lebeau was not interested. Havelaar proclaimed rightly: '[he is] the man who pursues the gold, not for the money, but for the illusion of the gold itself (...).'

The vase on the main photo is exhibited at Kunstconsult's sales exhibition Gestolde Dromen IX.

Click here for an overview of objects by Chris Lebeau in our collection.

This article was written by Jan de Bruijn and was previously published in Art Deco magazine (nr 12, winter 2015/2016). For this he made use of the book Chris Lebeau (1878-1945), written by Mechteld de Bois and published in 1987 by the Drents Museum.

© Kunstconsult – 20th century art | objects

Reproduction and distribution of this text is only allowed with correct reference.