RAM-ceramics of Theo Colenbrander

Why did idealistic and artistic people invest a quarter of a million guilders in an earthenware factory from Arnhem to realise the designs of an eighty-two-year-old artist? This question fascinates Arno Weltens, biographer of decorative artist Theo Colenbrander. At least the artistic result was worth their investment: RAM-ceramics are still valuable after almost one century.

There can only be one explanation for why Theo Colenbrander (1841-1930), the first Dutch industrial designer, was offered this unique opportunity by investors. It seems they had put their faith in the vision of the pioneer of Dutch applied art. Building on his previous three-dimensional work, Colenbrander would reach his last artistic accomplishment in the period from 1920 to 1925 at RAM. And his designs could be executed almost perfectly due to technological developments.

Revolutionary forms

Thirty-five years earlier, during his work for the famous earthenware factory Rozenburg from The Hague, this wasn’t the case. In the period from 1884 to 1889, many baked pieces had running colours; especially the colours blue and green were a challenge for the factory. However, Dutch art lovers still recognized his revolutionary use of form, colour and decoration. Art critics and fellow artists were wildly enthusiastic. But merely a limited number of buyers appreciated his artistic expressions.

This was even more so for the many tapestry designs that were produced by freelancer Colenbrander. While an eccentric looking vase or platter could fit into an interior of that time, a handcrafted tapestry by Colenbrander could not. The unusual, bright colours and sometimes bizarre patterns would quickly detonate with the furniture. Modernising a complete interior seemed like the only option. ‘Artichoke’ and ‘Swamp’ were his only designs that became a commercial success. These tapestries, initially manufactured at the Tapijtfabriek Amersfoort (tapestry factory of Amersfoort) and subsequently at the Deventer Tapijtfabriek (tapestry factory Deventer), were available in several variants.

Self-willed man

The originality of his sketches for ceramics, tapestries, interior designs and book and magazine covers, can be traced back to the person itself. Colenbrander was a self-willed man. Educated as an architect, but working as an overseer and technical draughtsman, he chose the uncertain life of a decorative artist at the age of forty-four.

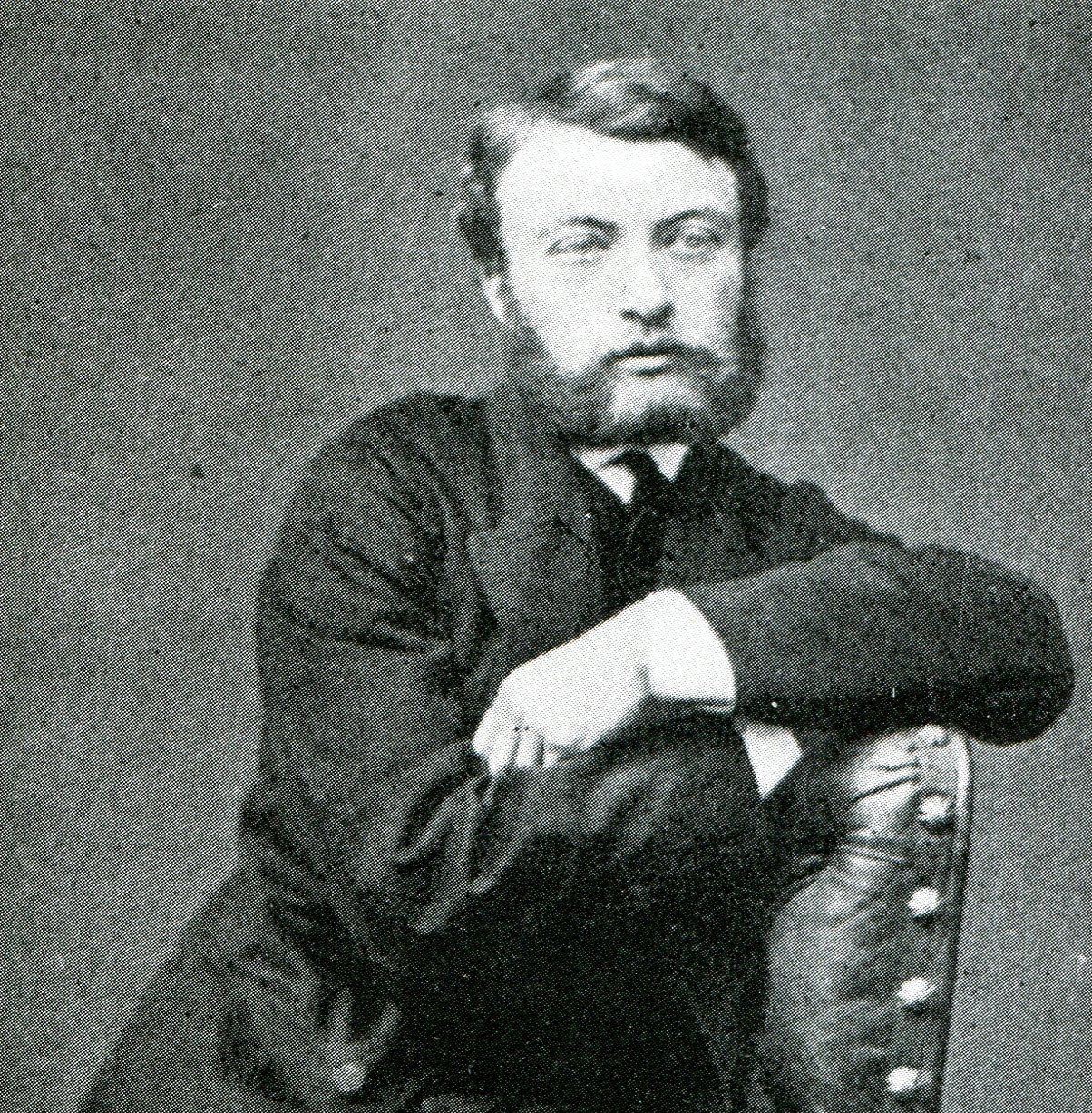

As an artistic visionary he frequently came in conflict with members of the board that were responsible for business policies. Consequently, his contract as an artistic leader at Rozenburg and Zuid-Holland ended with a dispute. His work as a designer of new patterns on existing earthenware at the earthenware factory Zuid-Holland in Gouda was even restricted to one year (1912-1913). Colenbrander was very introverted, but still surrounded himself with a select group of friends. Several times, journalists attempted to lure him into an interview in vain. Merely one photographic portrait of him is preserved. The Doesburg-born artist was averse to public appearances, something that was strikingly demonstrated in 1923, at an honorary exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam that was organised especially for him. The main character was missing, and not because of his age or the long journey from Arnhem to the capital; a few days after the opening Colenbrander did travel to Rotterdam to visit his friend and painter Gerke Henkes.

Process and assortment

For RAM – a Dutch reference to the astrological sign ‘Aries’ – Colenbrander manufactured approximately sixty different forms, for which he designed around seven hundred decorations. The fundamental idea was to incorporate nature, especially flora, whereby he abstracted the forms of plants and flowers. The base – ranging from a creamy to a yellowish undertone - was essential to his design as well. The RAM assortment consisted of a wide range of products, with the highlights being the five and three pieced ‘kaststellen’ (sets of ornamental jars) he designed. In 1925, the earthenware factory acquired a golden medal at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels modernes in Paris for ‘Cathedral’, a decoration he designed for a ‘kaststel’.

Some of these sets consisting of lidded vases and cups are part of the collections of Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam and the Museum of Modern Art in Arnhem. However, smaller and cheaper objects, like bowls, cups and even – RAM-ceramics were not utilitarian objects, but decorative earthenware – a flower pot.

With a pencil, Colenbrander personally applied the patterns on a bisque model vase. Subsequently he filled in the decor with watercolours. In the studio, Wim van Ham, ceramic painter and Colenbrander’s right-hand man, made sure the patterns were applied onto the models by means of stamps. Eventually, the desired colours were painted on by painters in the factory.

Enamel paints, not oxide paints

In 1923 a dispute arose with director Van Lerven about the choice of paint. The application of enamel paints was distinctive for Colenbrander earthenware at RAM. The artist wanted surfaces to be filled in opaquely. Van Lerven thought he had found a cheaper alternative, that is the use of oxide paints, which could be applied in a thinner and lighter way. Colenbrander completely disagreed with the experiments and reacted furiously. He despised this new type of paint, because according to him they did not go with his patterns. Initially, this alteration escaped him, because he was hardly present at the factory. Eventually, the artist brought back the use of enamel paints; the oxide paints were used in 1923 and 1924 only. Remarkably, this difference in execution is not reflected in the initial and present trade prices.

Development price levels

The selling prices were already high during the production of RAM. In March 1924, an art reporter at the open house of an auction of A. Mak in Amsterdam sighed that ‘The earthenware factory RAM ordered for the sale of Colenbranders earthenware, because the retailers found this handmade work too expensive, and could earn more from factory-made products’. However, according to museum director Van Erven Dorens from Arnhem, auctions were a deliberate way to bring these objects to the attention of the public. The initiators behind RAM wanted to ensure that the earthenware could be bought by as many art lovers as possible.

At the auction, Van Erven Dorens bought a pair of 30-centimeter-high elliptical vases with a decoration named “Rocks” for 44 guilders. By way of comparison: one similar vase with a decoration named “Market” yielded 4800 euros at Christie’s Amsterdam in May 2007. An auction result of 33 years ago noted 950 guilders for a pair of 8-centimeter-high bowls with a decoration named “Elegant”. The most remarkable result in terms of revenue is 16.730 euros for a 60-centimeter-high vase with a decoration named ‘Strength’, that was sold at an auction in Amsterdam in 2002.

Shift

It is quite remarkable that there has been a shift in auction results since the eighties. Initially, the prices of Rozenburg were above the level of RAM; nowadays the opposite is the case. This makes Colenbrander’s work from this period not only artistically, but also financially a valuable possession.

The fact that ceramics by Colenbrander have been in the spotlight for the last 125 years, shows that this artist is not an outdated phenomenon. The artistic inheritance of Colenbrander is, and will be, reserved for true enthusiasts.

About the author of this article

Author Arno Weltens calls himself a retrowatcher. He is the president of the foundation ‘Behoud Nederlandse Jugendstilarchitectuur’ (‘Preservation Dutch Jugendstil Architecture’) and wrote books about the earthenware and tapestries by Colenbrander and many other subjects. He also assists museums with curating exhibitions. For example, he was the force behind the ‘Theo Colenbrandersalon’ in the regional museum De Roode Tooren in Doesburg. Furthermore, he is an image researcher for the public service channel. A six-minute film about Colenbrander made by Weltens is available on YouTube. In 2014 he published a biography about the artist: Theo Colenbrander 1841 – 1930. (Uitgeverij Wbooks, ISBN 9789462580084)

Exhibition

The exhibition Biscuits by Theo Colenbrander will be on show until June 2nd at Museum Gouda. Models that Colenbrander made in biscuit earthenware as an example for the painters give a glimpse into the process from design to production of earthenware in Gouda and Arnhem.

Text: Arno Weltens

© Kunstconsult – 20th century art | objects

Reproduction and distribution of this text is only allowed with correct reference.