Jan van der Vaart: Pottery is a craft – glazing a science

Just before his death, Jan van der Vaart (1931-2000) had tactically placed his greatest success under embargo: his self-discovered and refined bronze glaze was not allowed to be revealed. The glaze, which he applied to countless vases and other stoneware, was declared secret from recipe to glaze test. Now 25 years later, this embargo, which was considered a patent by the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD), has expired.

In the magazine Vormen uit Vuur, Jan van der Vaart’s secret has been revealed. In collaboration with the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, extensive research was conducted into the structure of his bronze glaze. Shards featuring his characteristic bronze glaze were examined and studied closely. Through this research, the composition of the glaze was uncovered, and thus Van der Vaart’s long-kept secret was finally found. The text below contains a summary of the research and the findings regarding the famous bronze glaze.

Experimental Ceramist

Van der Vaart was, in a sense, self-taught and therefore did not have an academic background. The only formal training he received was a ceramics course at the Vrije Academie in The Hague. He learned from Theo Dobbelman and Just van Deventer over the course of twenty Saturdays (between November 1953 and March 1954). Beyond that, he relied on textbooks and other literature to educate himself in ceramic art. Remarkably, Jan later taught at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie—something quite unusual for a self-taught artist.

His lack of traditional schooling gave him a great deal of freedom in his work, and as a result he experimented extensively. He was someone who collected clay from riverbanks, scooped ash from fireplaces, and discovered new colours by creating his own glazes. Above all, he searched for the perfect bronze glaze. He stumbled upon it by accident in the 1950s—a discovery documented in his extensive and nearly unparalleled archive.

Newly Accessible Archive

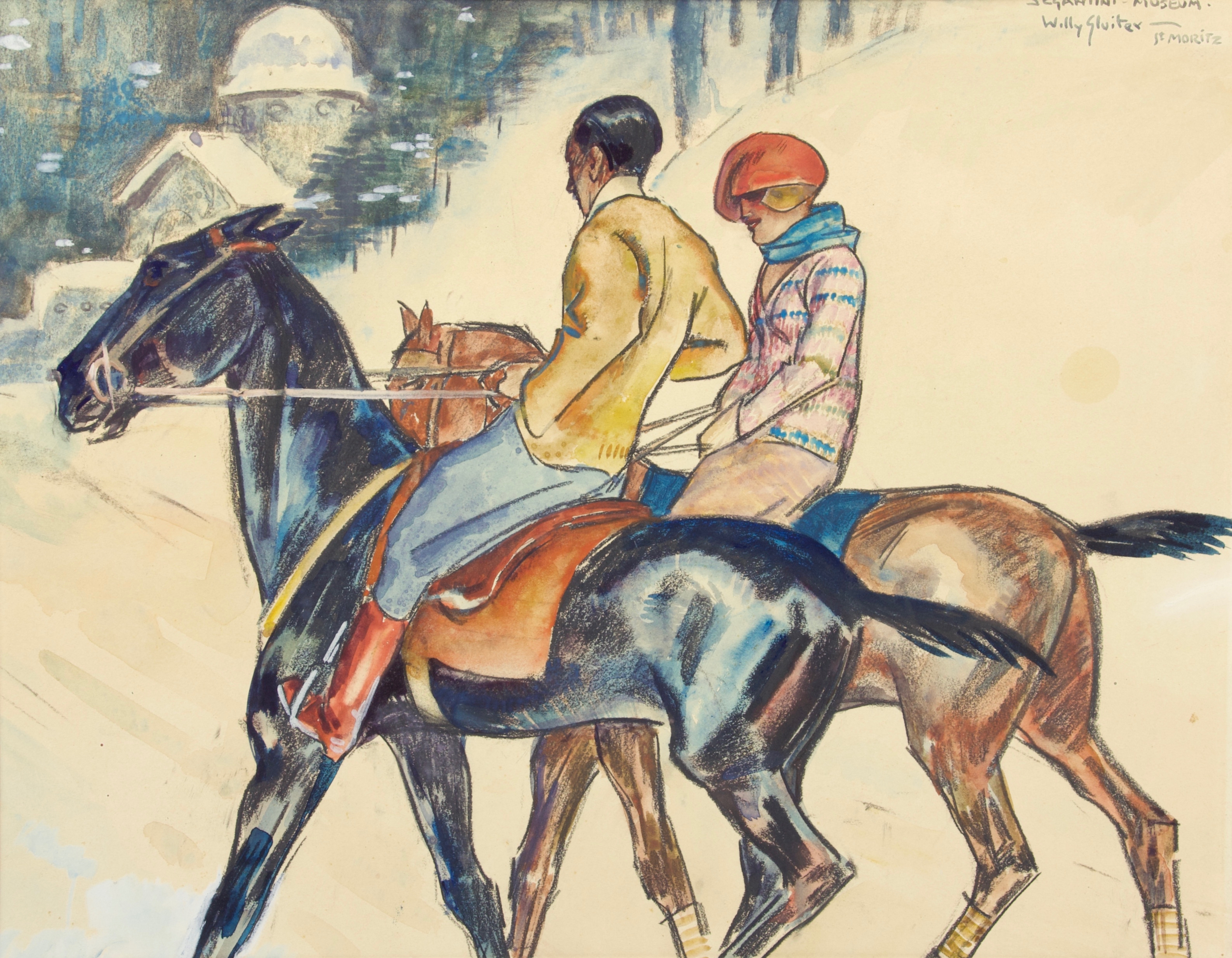

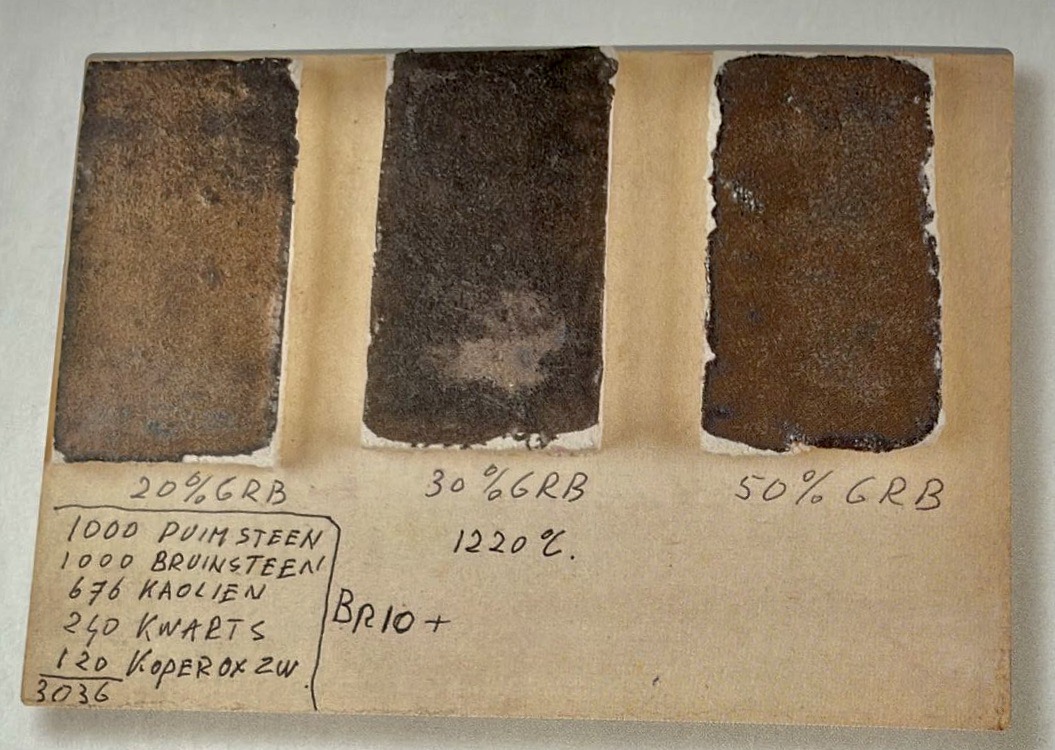

In 2025, the Van der Vaart archive was reorganised. The patent had long expired, and the non-disclosure restrictions were lifted. The now-accessible archive contains countless clay and glaze tests, notebooks, and binders. Thanks to the combination of handwritten clay and glaze recipes, notes, and physical test pieces, this archive is almost unique. Early glaze formulas paired with glaze samples mounted on pieces of cardboard reveal the investigative methods Van der Vaart used. The archive shows that Van der Vaart worked in a highly experimental manner. His research focused on the right composition of materials, firing temperatures, and clay percentages. He kept extensive logs so that each experiment could advance the previous one. Interestingly, the two best-preserved experiments—likely his most valuable research—lack any written recipe. These are square-mix tests for sinter engobes, some with bronze effects, which illustrate his investigation into the bronze glaze.

Image 1: Arcive Jan van der Vaart, 3 bronze glazes pasted on cardboard, image from 'vormen uit vuur'

In collaboration with the RKD, X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) was performed to determine the glaze composition and better understand Van der Vaart’s methods. This revealed various iron ions, potassium, calcium, manganese, copper, and lead. While this showed which substances he experimented with, further research was needed to uncover the cause of the bronze effect itself.

Image 2: Arcive Jan van der Vaart, 25 square mixing tests for sintering gobes, partly with bronze effect, pasted on cardboard, circa 1960. From 'vormen uit vuur'

Closer Look at the Bronze Effect

Visually, the shimmering “bronze” appears to arise from the structure of the glaze layer. A piece of stoneware with a glittering bronze surface was examined with an optical microscope under white and polarised light. Under white light, microscopically small crystalline configurations were found on the glaze surface. Polarised light revealed that the crystals grew in various directions—either parallel to or at an angle to the glaze surface. To identify the crystals further, the bronze glazes were analysed using X-ray diffraction (XRD). A match was found with a specific form of the chemical compound copper manganate (copper-manganese oxide), which belongs to the mineral group known as spinels.

Image 3: The bronze glaze of a glaze test, viewed with an optical microscope under white light. From 'vormen uit vuur'

After zooming in on the bronze glaze at the electron level, the microstructure of the crystals became even clearer: they consist of copper manganate that also contains iron and sometimes cobalt. Remarkably, the copper and manganese appear in a distinctive one-to-one ratio uncommon for spinels. The precise ratio of iron and/or cobalt relative to the copper seems directly dependent on variations in the bronze-glaze recipe combined with specific firing temperatures.

Glaze Scientist

Van der Vaart repeatedly achieved the crystallisation of minerals through his methods. He experimentally created copper manganate—a material whose colour resembles unpatinated bronze metal. The shimmer in the material results from the orientation and distribution of the tiny copper-manganate crystals. The crystals scatter and reflect light, explaining both the glimmer and the matte gloss of the bronze effect. The characteristic colour and crystal formation together achieve a perfect translation of the bronze effect into glaze.

Van der Vaart discovered the bronze glaze by accident in the 1950s and spent the 1960s refining it experimentally. We already knew he had found it, but only now has the “how” finally been uncovered. Twenty-five years after his death, it appears he discovered a method to crystallise a specific mineral. Copper-manganate spinel containing iron and cobalt has not been scientifically described before, making this a new discovery. It is not yet considered an officially recognised mineral. With this, Van der Vaart proves to be not only a master potter but also a glaze scientist. The bronze glaze thus gains an extra layer of uniqueness.

Image 4: Jan van der Vaart, Buttocks vase, 1988, from the Kunstconsult collection. Here the bronze glaze is perfectly executed.

New Admiration

This year, the scientific potter is given a new stage: since 15 November 2025, Kunstmuseum Den Haag has presented a retrospective Van der Vaart exhibition featuring more than 150 objects. The exhibition runs until 5 July 2026. One object from the Kunstconsult collection is also on display. The exhibition coincides with the publication of Jan van der Vaart: Meesterpottenbakker, a beautifully illustrated monograph on his life and work, published by the new art-book foundation Cometa*.

Image 5: Jan van der Vaart and Herman Gordijn, Jazz vase, 1955, from the Kunstconsult collection. This object will be shown during the exhibition in Kunstmuseum The Hague

The simultaneous emergence of the newly accessible archive and the exhibition at Kunstmuseum Den Haag does not mean that one resulted from the other. It is purely a coincidence. Interest in Van der Vaart had been simmering for several years. With the retrospective exhibition and the unveiling of his bronze-glaze secret, enthusiasm for Van der Vaart within the Netherlands is once again rekindled. Kunstconsult joins this renewed attention: our extensive collection will be on view during the sales exhibition on 20, 21 and 26–28 December.

Text by: Ariane Waitz